Falling Out

A friend recently asked about something I wrote on Stan Brakhage and Guy Davenport’s friendship, a piece that largely exists largely to quote Davenport’s exuberant letter to Hugh Kenner on first encountering Brakhage’s films. At the time of writing I hadn’t seen this 1965 essay by Davenport, for the National Review of all places, in which he judges Brakhage’s films the crowning achievement of the previous decade of American art. “Brakhage,” he winds up, “a tall Kansan who reminds one of a pony express scout, began his career, after trying various modes of film work, with a startling and beautiful movie called Anticipation of the Night. There had been nothing like it before…”

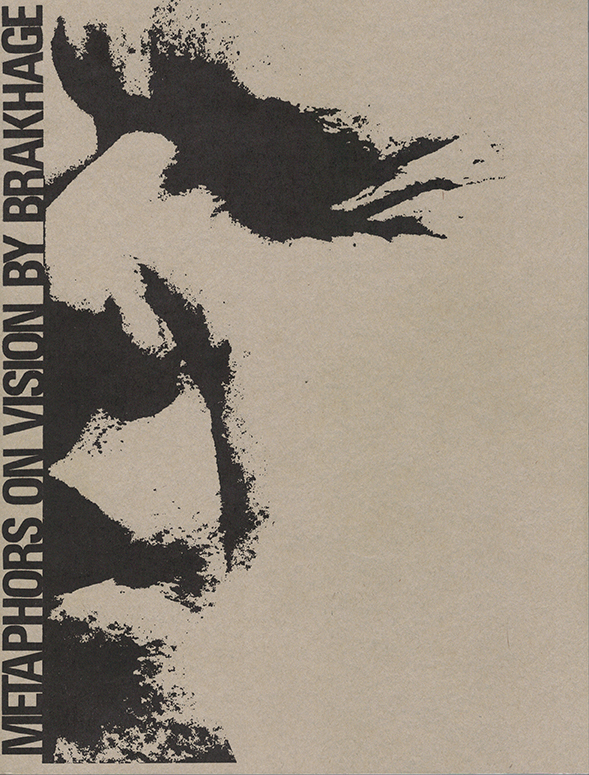

This was originally published in Canyon Cinemazine #6.

Friendly Fire

Over a long period of months in the mid 1980s, Jane Wodening—then Jane Brakhage—listened and made notes as her husband recounted the painful particulars of his early years. A practiced storyteller in her own right, she then worked this raw material into a memoir narration with the magic quality of fable. The couple separated a few years later, and the text, after being partly serialized in Motion Picture, was left in the drawer until 2014. Already a dual act of retrospection, Brakhage’s Childhood (Granary Books) comes further compounded by a lengthy afterword by Tony Pipolo, a film historian and psychoanalyst who quite reasonably takes Stan Brakhage’s recollections as occasion for analysis. In the course of his probing essay, he seizes upon the filmmaker’s falling out with the writer Guy Davenport, which occurred at roughly the same time as these memories were initially put into play, as being indicative of a strong tendency towards pathological narcissism. The circumstances of that schism, which involved Brakhage undermining Davenport’s chances at a MacArthur and then denying that he did any such thing, make for mortifying reading even at this distance.

Nevertheless, I cheered at the thought of this friendship in bloom. What common ground! Quite by chance, another years-in-the-making volume has appeared to restore some of what was lost in the fire. This would be Questioning Minds (Counterpoint), a two-volume set of Davenport’s correspondence with Hugh Kenner, edited with incredible stamina by Edward M. Burns and weighing about as much as a small bowling ball. Davenport’s friendship with Brakhage is only one of many such relationships detailed in the book, but it is an important one, requiring some two-dozen lines in the index and a discrete paragraph in Burns’ attentive introduction. Happily, we may now balance Pipolo’s account with Davenport’s own exuberant opening salvo, dated 1 May 1963:

This letter already too long, but see addendum’d page for irrepressible enthusiasm. Namely:

Stan Brakhage, maker of movies. He was here last week. He showed the Prelude to a film (probably five hours’ long when finished) that had a whallop like all new and unsuspected excellence. His early movies were so-so, and a nice beauty (all collage and double exposure) about Pere-Lachaise, if that be the spelling of the great Parisian cemetery, left one unprepared for the Prelude. Now my one motor skill is seeing. I know from post-mortems on movies that I see more than the average fellow. BUT the tax on my eyeball was the most demanding I’ve ever experienced, and Brakhage was pleased that somebody was looking at the film. Roughly outlined: a paced metric of briefly-held images, always a superimposition of two, but so arranged that the eye (so slow to lose an image) is always looking at four at once. Source of inspiration? The Cantos of EP. Hence a long and excited talk with B. until all hours of the morning, surrounded by students who carefully drifted away as the talk went haywire in their dull little noggins. The film itself gave up nothing but kaleidoscopic images to the inattentive. I didn’t know what some of the images were until I asked later (the lung’s inner surface, tripe-white and tripe-textured, puckering with exhalation, bubbling like boiling milk with inhalation; corpuscles photographed in perspective, enlarged 2000 times, the shiney red surface of a beating heart). The technical problems of photography were staggering. Sun-surface tidal fire, another image. Many trees in all weathers and all conditions of foliage. A lady’s face in orgasm. These the major recurring images, but when he had made a crescendo of them and the mind couldn’t take in anymore, a magic snowscene, conifers in snowlight, sifting snow, utter peace. The film was clearly a POEM (no other form will answer), so thick of imagery that only Tchelitchew the Rooshian painter and EP in Pisans forward have ever managed such intricacy. Two years in the making. Brakhage is immensely intelligent and humble, a slogging worker. His work only gets by at the ultra-snooty fillum societies. His ideal is for people to own his films (they’re 16MM) as one owns a painting or a collection of poetry books. Damned right, too.

The next part of the film (no title yet) I’m being sent, to show on my wall. When you look at my poor pome you will see how Brakhage and I sustained a longer conversation on flowering trees (aliter nymphs or entwives): he has them throughout his film, and knows what they mean in Tolkien and Greek poetry.

Needless to say, Haverford was bored to tears by brother Brakhage and half the audience left as the only true and real magic I’ve ever seen in films was unfolding on the screen. B. knows the Activists, especially Olsen, but cd never get the nerve to see Ez at St Liz. I must write something about him (he has filled the entire next issue of Film Quarterly with an essay on his work), and I suspect that you would palpitate to see the beautiful Prelude.

B’s a baby, a mere 30, self-educated (he stuck out two weeks at Dartmouth and fled). He has resisted the temptation to film Hitchcock’s TV work under H’s name. He lives in a ghost town in Colorado, with wife and 4 kiddies. Complex, deep, and rich, Mr B.

Davenport’s letters, it ought to be clear, are totally wonderful. “[They] are the best that have ever blessed me,” New Directions publisher James Laughlin gushed—and he would know (the letter goes on, “Ezra’s were too jumpy, and Rexroth’s were too vituperative. Yours have the best style and the way the phrases are assembled is magical.”). Reading Davenport’s report to Kenner about how Brakhage sent along “a yard of film from his newly finished movie…entitled Moth Light,” certainly brings back some of the initial excitement of a long-since canonized work, but perhaps more significant is the way the whole question of character is made freshly vivid reading offhanded observations such as this: “[Brakhage] thinks nothing of putting the family, the cameras, and cat and dog in his car and driving a thousand miles to sit in a man’s kitchen and talk about poetry or whatever.”

Davenport did in fact publish some of his impressions of Brakhage’s Songs in a 1966 article for Film Culture, but I can’t help but feeling that we are missing a more sustained meditation along the lines of those found in collections like Every Force Evolves a Form, The Geography of the Imagination, and The Hunter Gracchus. “He is one of the wizards,” Davenport wrote of Brakhage, and how I do wish he made closer study of the spells.[1] We know Brakhage wished to make his films widely available for home use, and in Davenport he had an ideal reader, not likely to be dominated by his genius but more than willing to place the work in a generous intellectual context.

Truly, the glories of friendship are neglected at our peril. Davenport and Kenner had their own falling out, it seems. After thousands of pages of correspondence, there followed long years with barely a postcard. “The intricate texture of their friendship suffered a rupture never explained in these letters,” Burns sagely observes.

[1] Not that they went entirely unacknowledged. Decades later, reflecting on his own style in an interview for The Paris Review, Davenport remarked: “I took my method of collage from Stan Brakhage and Gregory Markopoulos.”